Geddes TLV Non-Determinant ‘Garden’ City.

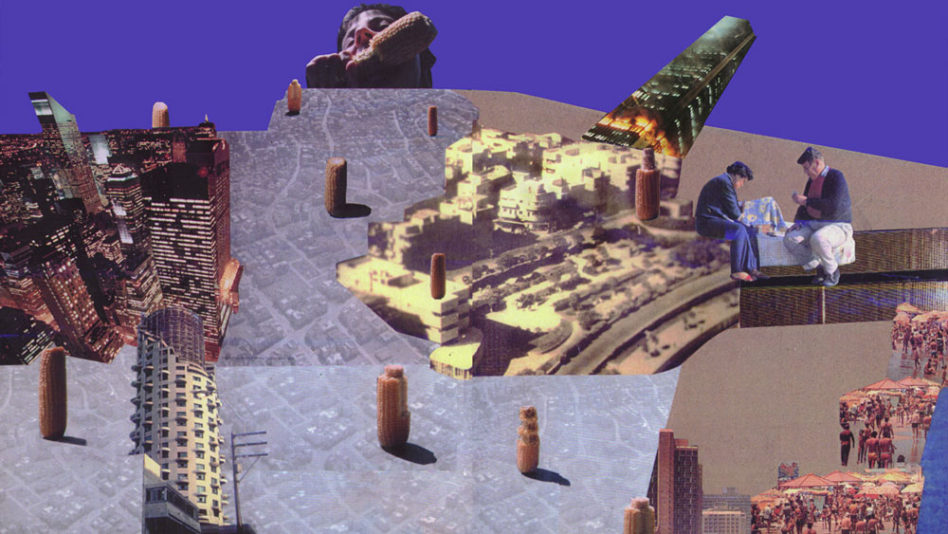

Conspicuously missing from contemporary planning is the question of the indeterminate. How to ‘design’ change and make degrees of freedom integral to urban development.

Within this context, Patrick Geddes’ plan for Tel-Aviv warrants revisiting as an exemplary early 20th century city plan, whose ‘logic’ continues to foster the city’s vitality and ongoing evolution into the 21st century.

Patrick Geddes: Void Planning

In a ‘Roster of World Cities’ published in 2000, Tel-Aviv was identified as the only Middle Eastern city exhibiting ‘strong evidence of world city formation’, ranking it behind alpha, beta and gamma metropolitan centers that form the nexus of global cultural and commercial hubs. Rather than focusing on sheer scale, the report classified cities based on their ability to successfully compete across an international service economy. Surprisingly, Tel-Aviv is positioned on par with Dublin, Helsinki, Luxembourg, Lyon, Philadelphia, Rio de Janeiro,Vienna and even ‘topped’ Birmingham, Manchester, Rotterdam, Athens, Seattle, Stuttgart, Brazilia and Vancouver among others. Upon closer inspection of potential ‘world-city runner ups’, Tel Aviv is the only early modernist ‘Garden City’ on the list of new contenders.

78 years after Patrick Geddes delivered the city’s first binding master plan, Tel-Aviv is showing signs of ‘intelligent urban life’ outside the major global arenas of North America, Western Europe and Asia. In revisiting the legacy of the Geddes plan for Tel-Aviv, the fact that it served as the foundation for a thriving urban, rather than suburban fabric, is its most interesting and lasting characteristic. In distinction from its early 20th century ‘Garden City’ counterparts, mid-century ‘Tower in the Park’ models, or deregulated sprawl, Geddes’ Tel-Aviv defies simple classification. The plan has seeded a one-off city. Dense, devoid of traditional hierarchies, lacking formal architectural specificity, spatially integrated and programmatically varied.

As one of the few built manifestations of Geddes’ social-evolutionary ideas, Tel-Aviv’s layout warrants closer inspection because it provided a non-determinant, adaptive and resilient development framework, introducing a design strategy that has exhibited relative ‘competitive-strength’ despite the plans small size, provincial location and absence of any local architectural or spatial precedent for its layout.

A singular evolutionary ‘drift’ of early 20th century planning, Geddes’ infrastructure and Tel-Aviv’s subsequent development challenge both the crises of the master plan and pessimism surrounding the possibility of forging new cities by design, while affording a critical alternative to overly picturesque and formalist urban design approaches, past and present.

Timing & Background

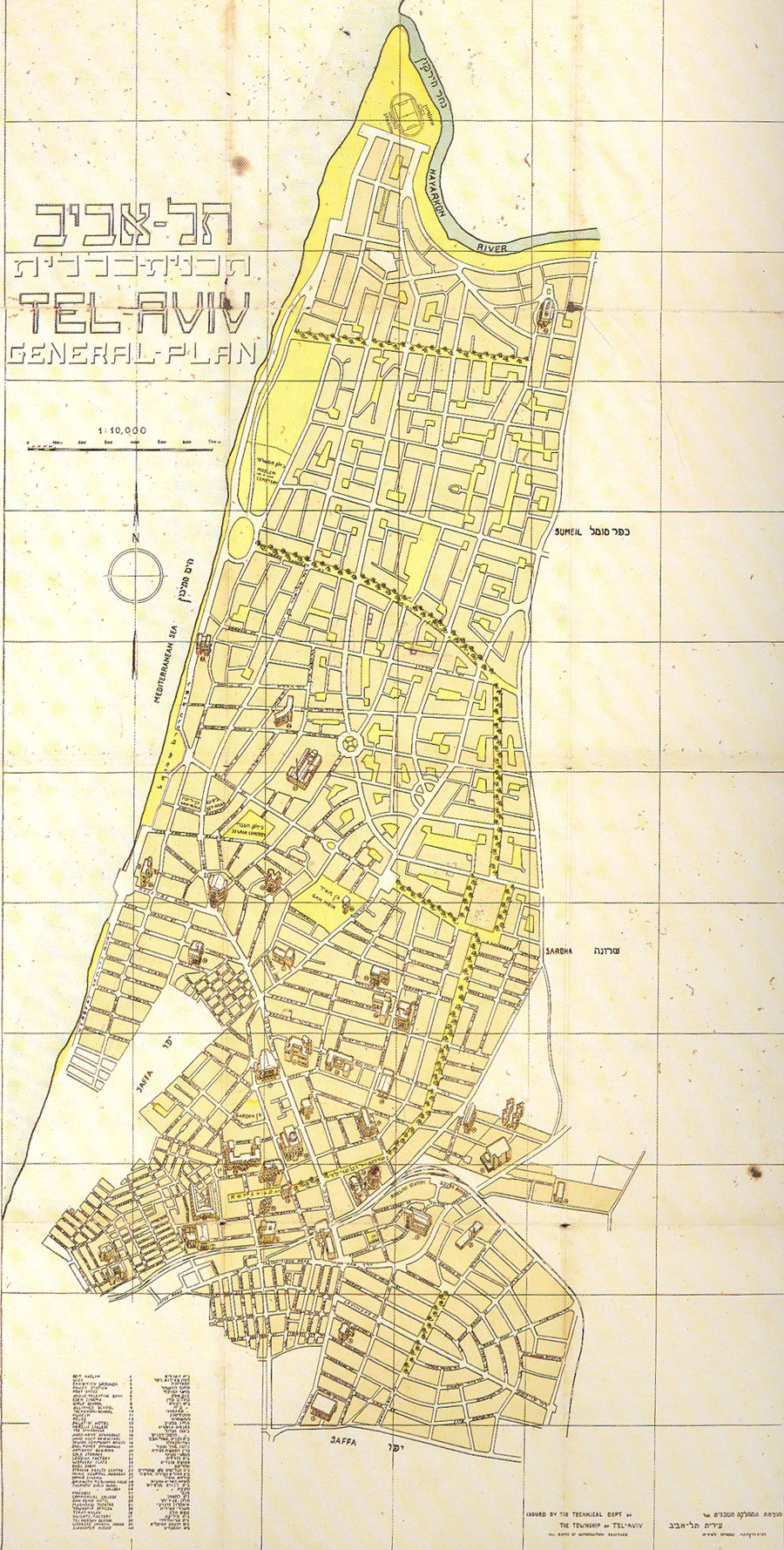

Patrick Geddes was invited to design Tel-Aviv’s ‘General Town Planning Scheme’ in 1921, approved in 1925. By that time rapid Jewish Immigration, inter-ethnic strife with Jaffa’s Muslim population and several haphazard attempts at the city’s northern expansion, set the stage for commissioning an independent plan for Tel Aviv’s growth.

Geddes’ first contact with the Zionist movement was established in 1911, following a town planning exhibit focusing on the relationship between social and cultural values and spatial layouts. Geddes’ regional planning treatise ‘Cities in Evolution’, published in 1915, further elaborated his holistic view of cities as organic, multi-tiered entities, tightly coupled with social dimensions. Drawing parallels between diverse structures of biological organisms and their environmental adaptability, Geddes’ survey of 19th and early 20th century urban forms focuses on the link between communities, geography, spatial layout and capacity to accommodate growth. Geddes’ utopian agenda, aimed at melding people, industry and the city met with a sympathetic audience of Zionist leaders. As part of the Zionist project Tel-Aviv’s plan was meant to root a ‘new society, a new environment, ultimately a new nation’ in the sand-dunes by affording a ‘wholesome’ and ‘green’ city.

So while the Geddes plan was conceived the same year as Le-Corbusiers’ ‘Plan Voisin’, rather than speculating on the potential of the automobile and modern tower construction to zone and decongest cities, Geddes’ plan outlined a civic ideal aimed at relating the garden, building and public infrastructure to an interconnected, multi-functional human scaled environment.

The Plan

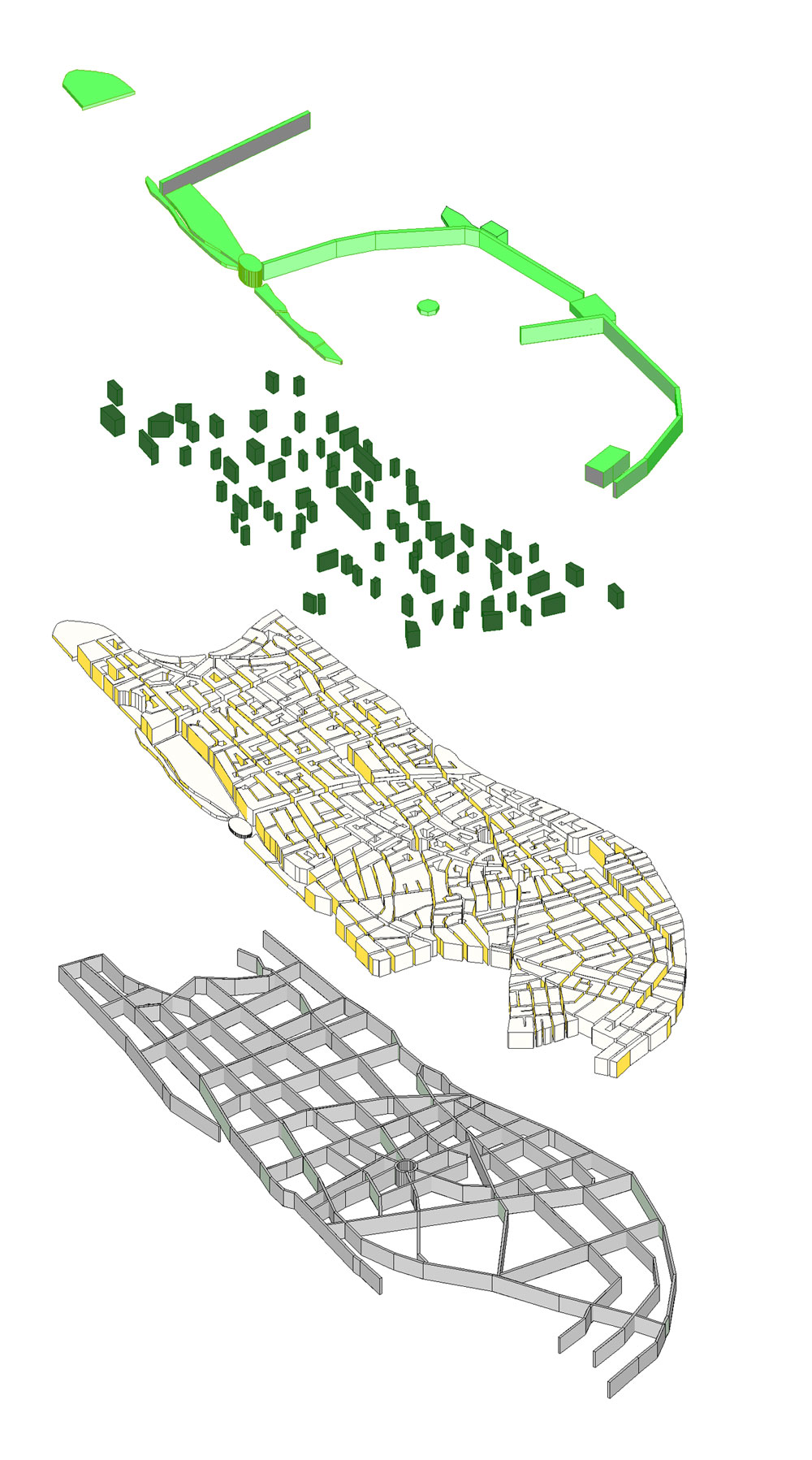

The Geddes plan was based on two months of active surveying in Tel-Aviv and six months of writing in Edinburgh, resulting in a detailed report and a diagrammatic layout of the city prescribing a multi-scaled infrastructure. The plan included specifications of individual lots; 70% building coverage, 4-6 story building heights, residential and commercial programs; interior block, super-block and neighbourhood civic green spaces; major traffic arteries and their respective sections; public boulevards, their planting schemes and sections, central public spaces, civic buildings and two waterfront parks.

Hybrid Grid & Spine

The plan outlines 7 major north south axes, stemming from the orientation of Jaffa’s historic street pattern and 10 east-west perpendicular streets forming a more-or-less rectilinear grid of large 300 meter super-blocks fronting the Mediterranean Sea. The interior of Geddes’ super-blocks represents one of the most significant innovations in Tel-Aviv’s plan, creating a medium for densification and a spatial framework capable of generating varied forms of occupancy, each with different life spans, within them.

The concept of a super-block was already in use at the time of Geddes’ plan, introduced by Raymond Unwins’ garden city model. By scaling the size of the block, locating traffic on the perimeter and creating a pattern of dead end streets on the interior, Unwin’s super-blocks aimed at resolving overcrowding and eliminating excess traffic to create a rural, grid-defying settlement pattern.

Geddes however rejected the cul-de-sac model devising a system of slow non-through traffic on the interior of the super-blocks, strung off the perimeter gridded main streets, in a pin-wheel fashion. To further discourage fast through traffic, the interior streets are mis-aligned and are predominantly one-way. In distinction from other garden city grid defying models like Lewis Mumford’s Superblocks, and Frank Loyd Wright Broadacre City, Geddes’ plan enables continuous circulation. Geddes’ differentiated street system, establishes a spatial pacemaker with ‘accelerated’ traffic and commercial uses on the main axes and ‘decelerated’ meandering residential programs within the interior of the super-blocks. By merely turning off of the main streets, to the interior of the super-block there is an accompanying shift of experience, from fast, to slow, from public and urban, to more private and residential. Melding the grid and the spine, the Geddes plan outlined both a generic, equal and continuous grid for Tel-Aviv’s development and a non-repetitive mosaic of interior blocks to accommodate different urban episodes.

Lots and Agglomeration

Geddes’ plan and Tel Aviv’s eventual building densities are derived from its individual lot system, based on narrow 25 meter plots, designed to house 4-6 story buildings, with 5 meters side setbacks and a front or back yards of 7-10 meters, leaving 30% of the lot for civic green. In addition to designating interstitial green spaces on each lot, several interior lots were to be kept open to form pocket gardens functioning as shared green spaces within the super-blocks. Individually, each open space was meant to facilitate local communal activity, while together the pattern of internal voids aimed at reducing overall congestion in addition to sequencing neighbourhood activities across super-blocks. De facto, only a third of the planned interior gardens were realised as a real-estate crash and the virtual bankruptcy of the municipality in 1926 prevented the public purchase of lots. The realised sequence of green gardens on the super-block interiors, function as fully accessible and intimately scaled spaces, for sporadic neighbourhood activity.

Despite the subsequent dramatic increase in building densities, reaching up to 80 units per 100m2 Geddes’ subdivisions have exhibited a high degree of resilience. Most of the initial development within the Geddes plan was based on single lot development and did not typically scale beyond the super-blocks’ internal subdivisions, sustaining the legibility of the Geddes layout and the primacy of its voids over the specific architectural morphologies filling the plan. The Geddes plans’ lot system, interior block formations and super-blocks, constrain development through a shared green civic infrastructure.

The range of green spaces from makeshift lot by lot front yards, to the internal super-block gardens and tree lined streets define an informal city. Geddes’ plan afforded a non-hierarchical infrastructure, pedestrian scaled assemblage of well defined super-blocks where civic green and buildings intermingle, mixing public-semi-public-private spaces, held together by a legible framework. Beside basic prescriptions of building scale, lot coverage and building setbacks, the architecture of Tel Aviv is moot. For the most part, the buildings are shoddily constructed, built using standard cheap concrete construction methods and materials, and basic details. With the exception of a handful of exemplary Oriental, Bauhaus and International Style buildings, the city is devoid of canonical architectural gems.

Programmatic Civic Nodes, Boulevards and Public Parks

Geddes’ boulevards, civic nodes, urban plazas and large scaled parks afford an additional layer in Tel-Aviv’s plan. Serving as the city’s central nervous system Rothchild, Hen, Ben Zion, Ben Gurion and Nordau boulevards afford planted shaded walkways stringing together a series of designated cultural and civic nodes, including, Habima, Heichal Hatarbut, Kikar Rabin and the Municipality and ending at the sea with Kikar Atarim.

Dizenegof circle, originally planned by Geddes as a hexagonal shaped urban space, was the only public nexus located off of the ‘green circuit’, serving as a loaded symbolic reference, Geddes commented that ‘the six sided figure alone lends itself to the full notation of life: Life organic, life social, life moral’.

Geddes’ plan also delineated a large green waterfront park, Gan Haatzmaut and municipal sports and recreation grounds at the northern edge of the city, linked by a seaside pedestrian and vehicular roadway.

In distinction from the continuous fabric, Geddes’ cultural Nodes, Boulevards and waterfront parks serve as climatized urban episodes providing larger scaled, shared, open, communally experienced spaces of civic awareness.

Porous City

Articulating a multi-layered spatial infrastructure comprised of in between spaces, slow streets, fast arteries, gardens, boulevards, plazas and parks, the Geddes plan enables the unfolding of a range of architectures and has exhibited resilience in accommodating a mix of residential, commercial and civic needs.

By systemising the un-built, the civic, the potential, the free, the accessible, the connected, the Geddes plan created a dense yet porous, non-hierarchical city infrastructure, establishing spatial coherence by securing the voids rather than prescribing built architectures, to foster its growth.

Postscript (2003)

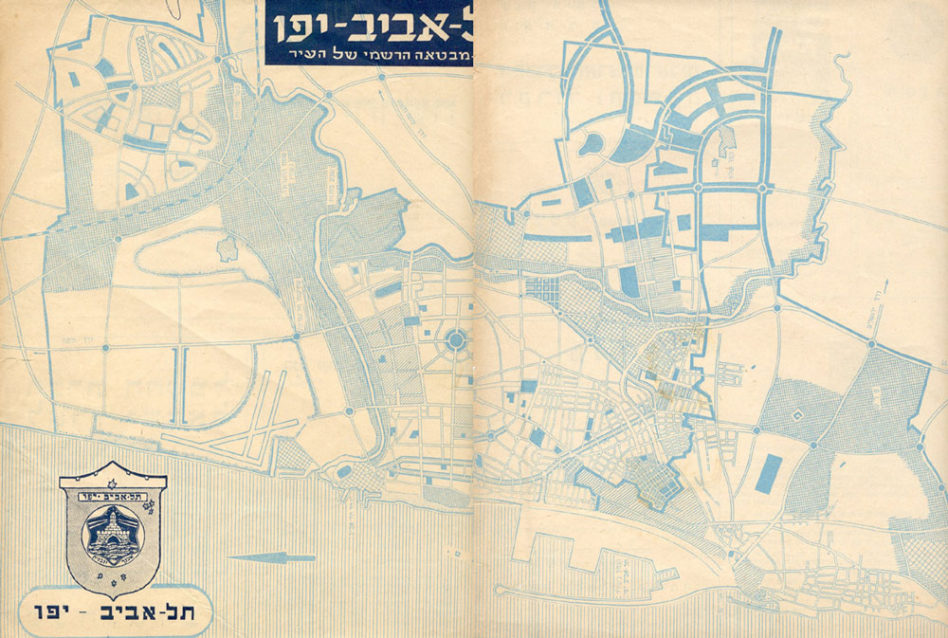

By 1938, the population of Tel-Aviv grew to 150,000 filling the extent of the Geddes plan with an influx of primarily German and East European city dweller immigrants.

In 1950, a modified municipal plan for Tel-Aviv marks the end of the Geddes plan’s urban and cultural influence in Israel. Tel Aviv’s future is envisioned as a series of isolated enclave neighbourhoods, inverting the logic of the seminal Geddes plan. An ensuing anti-urban sentiment prevailed in the planning of the Ramat Aviv, Shikun Lamed and Ezorei Hen as the northern extension of the city, creating middle-class bedside communities. The weaker southern and western neighbourhoods including Hadar Yosef and Jaffa were similarly isolated by design.

Rendering Tel-Aviv as a superset of neighbourhoods, rather than an urban continuum, the 1950 plan served as the city’s first step in its ‘disjointed’ future. Tel-Aviv’s growth and development has since evolved without a spatial infrastructure. An exquisite corpse of office towers and housing projects, with green and civic spaces serving as the residual, rather than a driving developmental force. Ironically, the approval of large scaled developments within the Geddes fabric are typically predicated on requiring that the developer refurbish and “preserve” an existing civic building, whereas the spatial infrastructure, Tel-Aviv’s most significant asset is rarely considered of value on its own.

Within the Geddes plan, the increased scale of real estate development in the late 1990’s-early 2000’s shifted from single or multiple lots to the scale of full super-blocks. These projects erase Geddes’ multilayered infrastructure and introduced gated green spaces, creating non-porous, architectural mammoths that cannot re-enter the logic of the city’s layout, undermining its ability to regenerate and reinvent itself. The resilience of Geddes’ plan ends with them.

Civic development regulations that increase lot building footprints have further encroached on the city’s civic greens. Block by block, the in between spaces, streetscape trees and vegetation are being replaced by concrete street fronts, eradicating Tel Aviv’s green future.